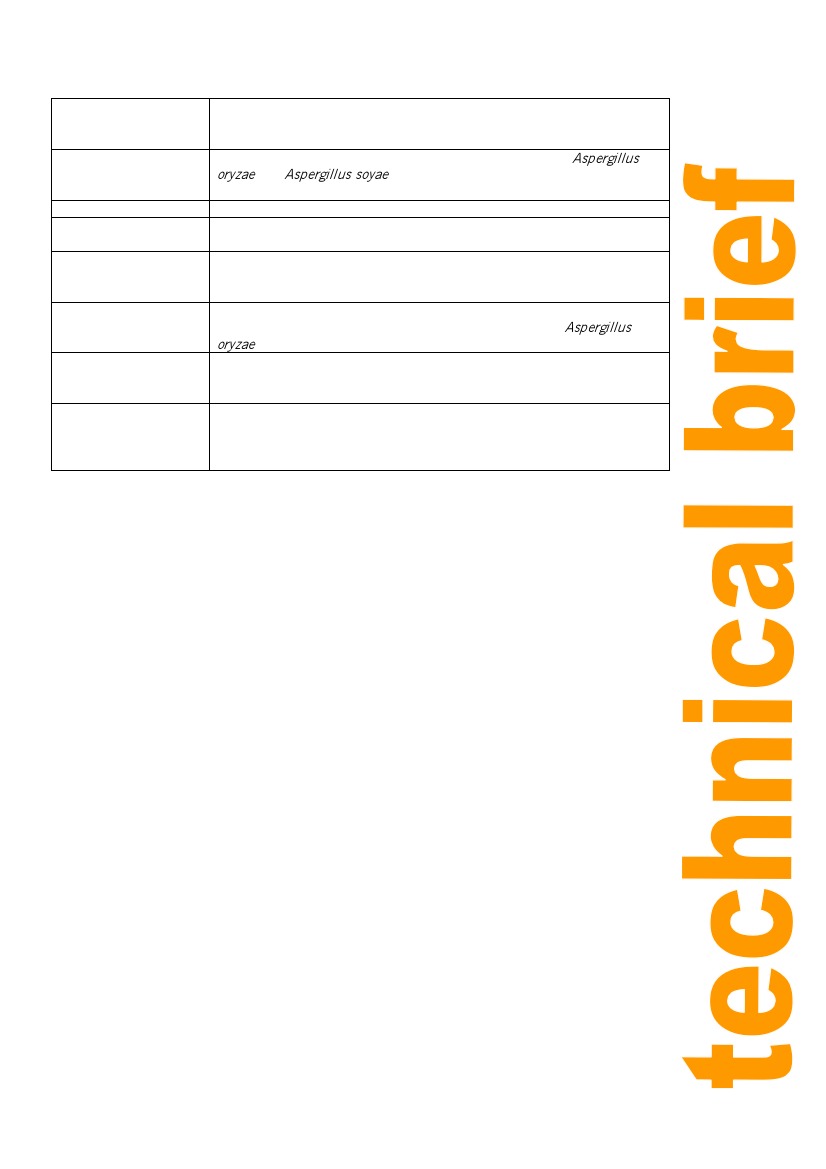

Fermented foods

Practical Action

Shiokara

Small pieces of strongly flavoured meat in a viscous brown paste, made

from heavily salted, fermented seafood viscera (e.g. cuttlefish, squid,

tuna, oyster, shrimp, crab or sea cucumber).

Soy sauce

A condiment produced by fermenting salted soybeans with Aspergillus

oryzae and Aspergillus soyae. All types of soy sauce are salty, earthy,

brownish liquids with a distinctive umami flavour.

Tempeh (or tempe)

A fermented soybean cake that has a firm texture and strong flavour.

Tian mian jiang

A thick, brown or black Chinese sauce made from wheat flour, sugar, salt

and fermented soybean residue from soy sauce production.

Tibicos

A drink made by bacteria and yeasts in a matrix similar to kefir grains.

The fermentation produces lactic acid, alcohol and carbon dioxide, which

carbonates the drink.

Tương

Different types of Vietnamese salty dark brown pastes or liquids used as

condiments, made from roasted soybeans fermented with Aspergillus

oryzae.

Viili A type of Nordic yoghurt with a ropy, gelatinous consistency and a sour

taste produced by lactic acid bacteria. Traditional cultures also contain

yeasts.

Zha cai (Sichuan

A spicy, sour and salty Chinese pickle (similar to kimchi) made from

vegetable)

salted, pressed and dried mustard stems rubbed with red chilli paste and

fermented in earthenware jars. It is washed before use to remove the

chilli paste and excess salt.

Table 1. Examples of fermented foods

(Adapted from multiple sources based at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fermentation_%28food%29)

Fermentations can be grouped into those that take place using solid foods and those that use

liquid raw materials. Most solid food fermentations use micro-organisms that require air to

grow and produce the characteristic flavours (i.e. ‘aerobic’ micro-organisms), whereas most

submerged fermentations using liquid foods require anaerobic conditions in which air is

excluded. This difference is reflected in the different production methods and equipment

described below.

Solid fermentations

Most solid food fermentations involve the growth of moulds, yeasts and/or lactic acid bacteria

on moist materials such as tubers, cereals, soybeans or meats, and also food-processing

residues (e.g. wheat bran, or soya flakes remaining after oil extraction). Traditional products

produced by mould fermentations include Indonesian tempeh and Indian ragi. Yeasts and

moulds are used to produce tapé, and yeasts and/or lactic acid bacteria produce raised bread

dough as well as fermented cassava and rice products.

The first stage is to prepare the food by shredding, grinding or flaking the material, and

sometimes by heating it to remove any contaminating micro-organisms. It is then inoculated

with the required micro-organism(s), either from bought cultures or using previously fermented

material. It is incubated within a specific temperature range and moisture content to allow the

micro-organism to grow into the food. Fermentations that are traditional to an area are

successful at ambient temperatures, whereas fermentations that are introduced from other

areas may require temperature control. This can be done by continuously mixing the food or by

blowing cool air through the material. Depending on the product, the moisture content is

usually maintained between 30-75% to allow maximum cell growth. The final product may be

the fermented material itself, or liquid components that are drained or washed from the

fermented material.

The simplest technologies for solid food fermentations such as kenkey, bread dough and gari

are trays, bowls or other containers of food that are incubated in a room or a cabinet. Many

types of sausage are also fermented in their casings (see Technical Brief: fresh and cured

sausages). At a larger scale, equipment known as a ‘bioreactor’ is used. Different types of

batch bioreactors include rotating or rocking drums, and stationary or stirred aerated beds. For

3