402 chapter 44

In every society, disabled children have the same social needs as other children.

They need to be loved and respected. They need to play and explore their world with

other children and adults. They need opportunities to develop and use their bodies and

minds to their fullest ability, whatever that may be. They need to feel welcome and

appreciated by their family and in their community.

Unfortunately, in most villages and neighborhoods, disabled persons—including

children—are not given the full chance they deserve. Too often people see in them only

what is wrong or different without appreciating what is right.

DIFFERENT COMMUNITIES REQUIRE DIFFERENT APPROACHES

The way people treat disabled persons differs from family to family, community to

community, and country to country.

• Local beliefs and customs sometimes cause people to look down on disabled persons. For

example, in some places, people believe that children are born disabled or deformed because

their parents did something bad, or displeased the gods. Or they may believe that a child was

born defective to pay for her sins in an earlier life. In such cases, parents may feel that to correct

a deformity or to limit the child’s suffering would be to go against the will of the gods.

• Lack of correct information often leads to misunderstanding. For example, some people think

that paralysis caused by polio or cerebral palsy is ‘catching’ (contagious), so they refuse to let

their children go near a paralyzed child.

• In many societies, children who have seizures or mental illness are said to be possessed by the

devil or evil spirits. Such children may be feared, locked up, or beaten.

• Failure to recognize the value and possibilities of disabled persons may lead to their

being neglected or abandoned. In many countries, parents give their disabled children to their

grandparents to bring up. (In return, many of these children when they grow up take devoted care of

their aging grandparents.)

• Fear of what is strange, different, or not understood explains a lot of people’s negative

feelings. For example, in communities where polio is common, a child who limps may be well

accepted. However, in a community where few children have physical disabilities (or where most

who do are kept hidden), the child with a limp may be teased cruelly or avoided by other children.

• How severe a disability is often influences whether or not the family or community gives the

child a fair chance. In some parts of Africa, children with polio who manage to walk, even with

braces or crutches, have a good chance of becoming well accepted into society. The opposite is

true for children who never manage

to walk. Even though most could

learn important skills with their hands

and perhaps become self-sufficient,

the majority of non-walkers die in

childhood, largely from hunger or

neglect.

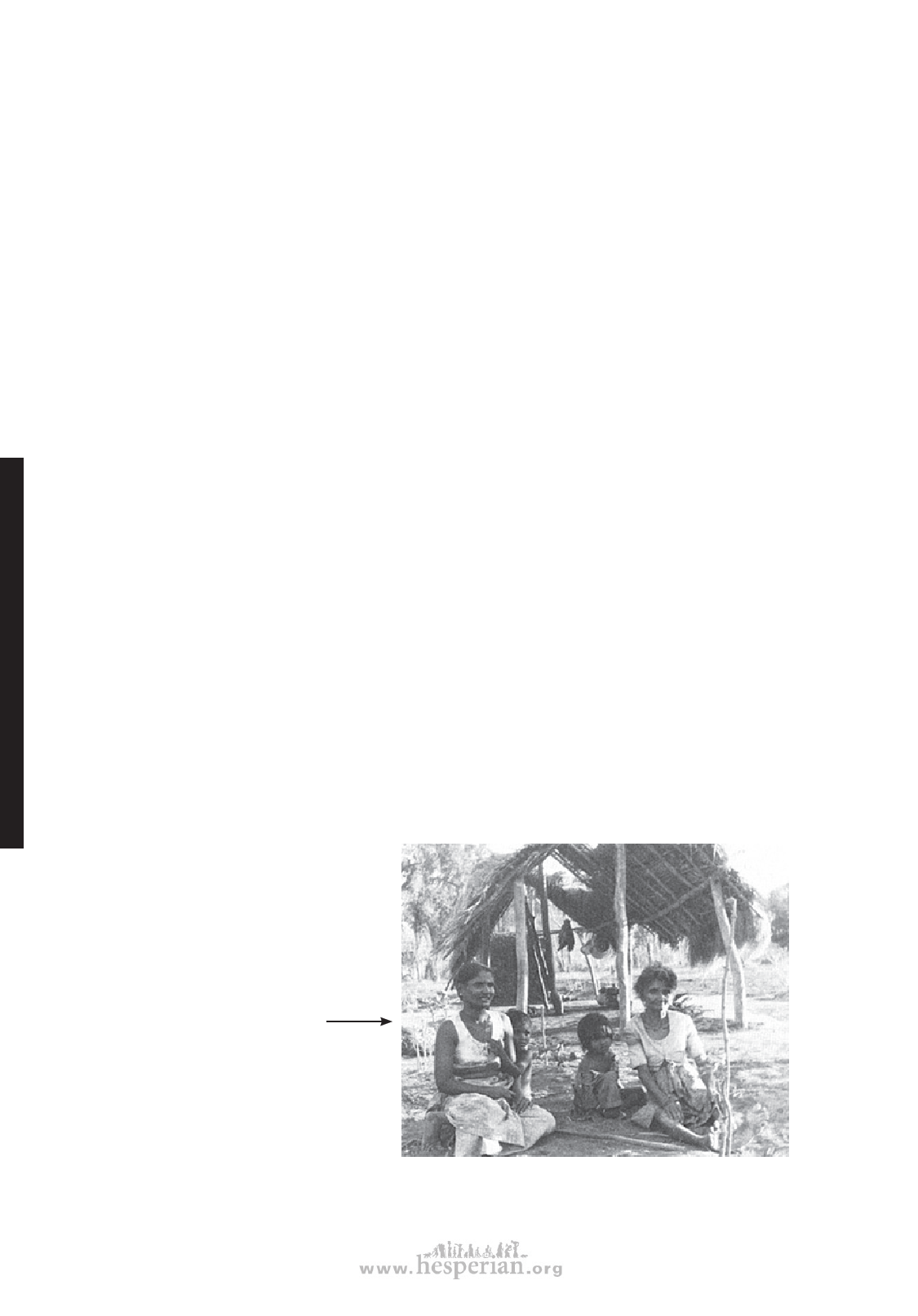

• Where poverty is extreme, a child’s

disability may seem of small

importance. When this family

in Sri Lanka was asked about

their disabled child, the mother

said her biggest worry was that the

roof of their hut leaked. The village

rehabilitation workers organized

neighbors to help build a new roof.

Only when the basic needs of food and

shelter were met, could the mother

give attention to her child’s disability.

(Photo: Philip Kgosana, UNICEF, Sri Lanka.)

Disabled village Children