404 chapter 44

But Mari does not want to go back to her own village. “It’s depressing there!” she

says. “I never go out of the house. I don’t want to. The people don’t treat me like myself

anymore. They don’t even treat me like a person. They treat me like a cripple, a nothing.

One time I tried to kill myself. But here in Ajoya it’s a different world! People treat me just

like anybody else. I love it here! And I feel useful.”

Her fellow team members in the village

rehabilitation center are trying to convince

Mari to go back sometime to her own village

as a rehabilitation worker. They offer

to help her change people’s attitudes

there, too. Mari is still uncertain. But the

PROJIMO team has begun to visit Mari’s

village. Already the families of disabled

children there have begun to organize.

The village children have helped build a

‘playground for all’, and adults have built

a small ‘rehabilitation post’ next to it. So,

things have begun to change in Mari’s

village too. The ‘different world’ has

begun to grow and spread.

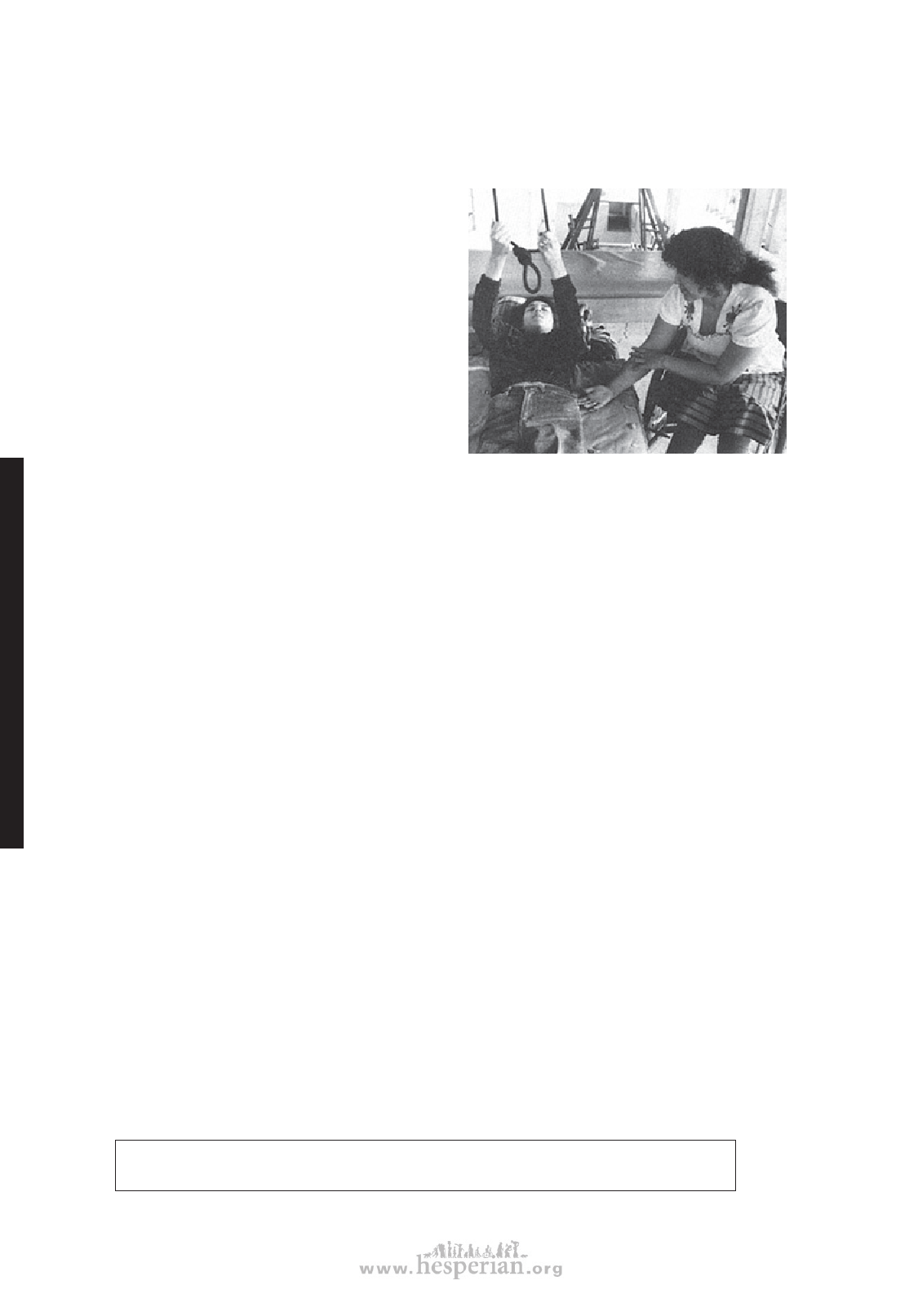

Mari helps another spinal cord injured

girl with her exercises.

In PART 2 of this book we look at ways to help the community respond more

favorably to disabled children and their needs. Usually, of course, a village or

neighborhood does not decide, on its own account, to offer greater assistance,

acceptance, and opportunity to disabled persons and their families. Rather, disabled

persons and their families must begin to work together, to look for resources, and to

re-educate both themselves and their community. Finally—when they gain enough

popular understanding and support—they can insist on their rights.

The different chapters in PART 2 discuss various approaches and possibilities for

bringing about greater understanding of the needs and possibilities of disabled children

in their communities. We start by looking at what disabled persons and their families

can do for themselves and each other. We look at possibilities for starting a family-

based rehabilitation program, and the importance of starting community-directed

rehabilitation centers run by disabled villagers themselves. We explore ways to include

village families and school children. Finally, we look at specific needs of the disabled

child growing up within the community—needs for group play, schooling, friendships,

respect, self-reliance, social activities, ways to earn a living or to serve others; also

needs for love, marriage, and family.

EXAMPLES, NOT ADVICE

In this part of the book, which deals with community issues, we will try mostly to give

examples rather than advice. When it comes to questions of attitudes, customs, and

social processes, advice from any outsider to a particular community or culture can be

dangerous. So as you read the experiences and examples given in these pages, do not

take them as instructions for action. Use, adapt, or reject them according to the reality of

the people, culture, needs, and possibilities within your own village or community.

Each community is unique and has its own obstacles and possibilities.

Disabled village Children