Overprotection

INTRODUCTION TO PART 2 403

Certainly not all disabled children are neglected or treated cruelly. In Latin America

(where this book was written) a disabled child is often treated by the family with an

enormous amount of love and concern. It is common for parents to spend their last

peso trying to cure their child, or to buy her vitamins or sweets, even at the cost of

hardship for the other children.

Providing too much protection is one of the

biggest problems in Latin America and elsewhere.

The family does almost everything for the child,

and so holds her back from developing skills and

learning to care for herself. Even a child with a

fairly mild disability is often not allowed to play

with other children or go to school because her

parents fear she will be teased, or unable to do as

well as the others.

Even in Latin America, where families

usually provide loving care for their disabled

children, they often keep them hidden away.

Seldom do you see a disabled child playing

in the streets, helping in the marketplace, or

working in the fields. Partly because disabled

persons are given so little chance to take part

in the life of the community, everyone assumes

that they cannot—and should not. Disabled

children often grow up as outsiders in their own

village or neighborhood. They are unable to work,

unable to marry and have children, unable even

to move about and relate freely to others in the

community. This is not because their disabilities

prevent them, but because society makes it so

difficult.

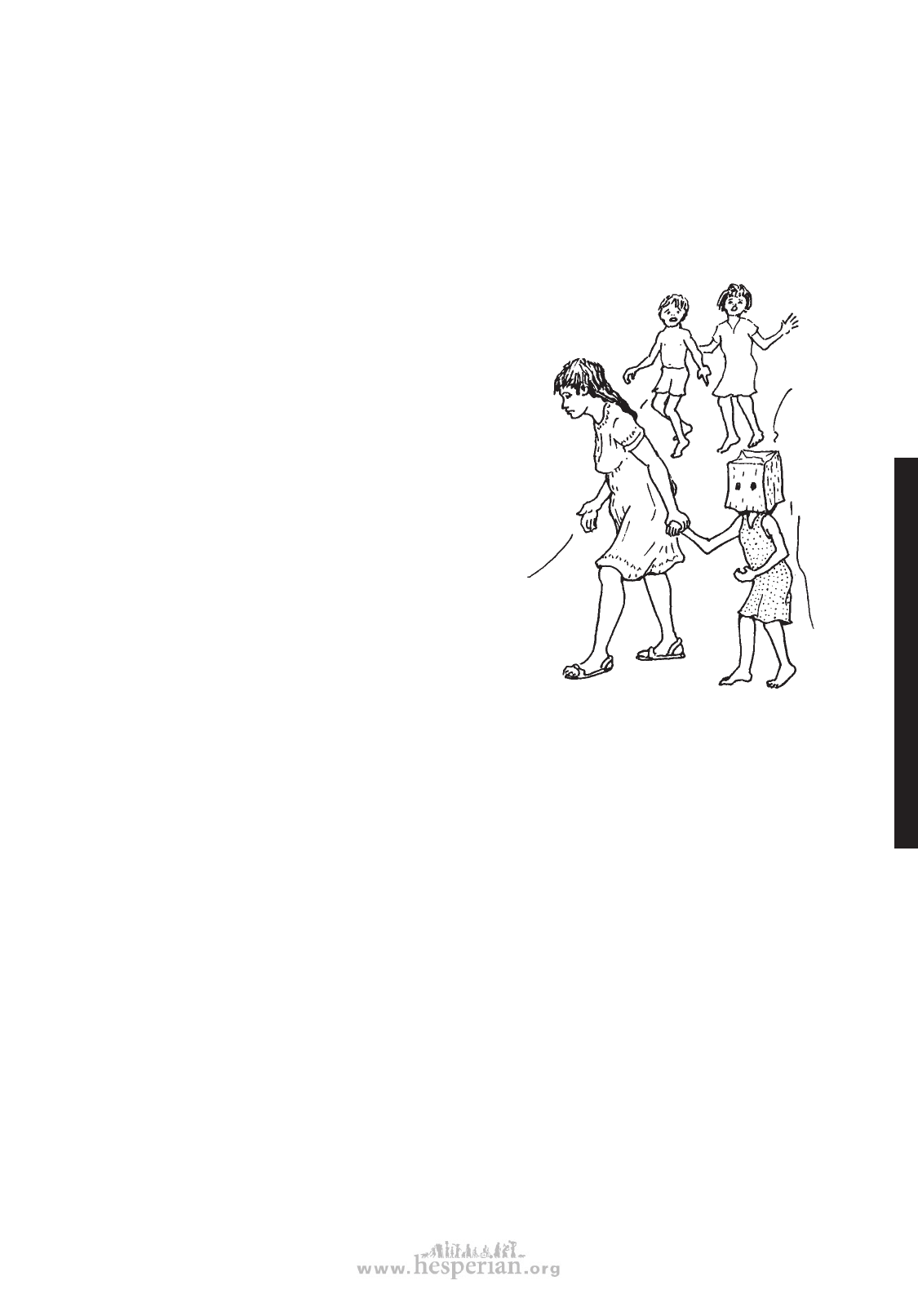

In one Latin American border town,

a mother brought her child to a

clinic with her head covered by a

paper bag—to hide a deformity of

her mouth (cleft lip).

Yet things do not have to be like this. In the village of Ajoya, Mexico, people used to stare

at, turn their backs on, or express their sorrow for the occasional disabled child whom

they saw. But now things have changed. Ajoya has become the base of a community

rehabilitation program (PROJIMO) run mainly by disabled young people.

In Ajoya, disabled children and their parents are now comfortable about being seen

in public. Non-disabled and disabled children play together in a ‘playground for all’ built

by the village children with their parents’ help. The community has helped build special

paths and ramps so wheelchair riders can get to the stores, to the village square, in

and out of some homes, and to the outdoor movie on Saturday nights.

Mari, a young woman who is paraplegic (paralyzed from the waist down), first came

to Ajoya from a neighboring village for rehabilitation. She soon became interested in

the village program and decided to stay and become a worker. Today Mari keeps the

records, helps interview and advise disabled children and their families, and is learning

how to make plastic leg braces. She has become one of the most important members

of the PROJIMO team.

disabled village children