9-8

• Attitudes toward people in need. (Does the student feel respect, kindness,

and concern for sick persons, old persons, women, children, and very poor

persons? Is he eager to share his knowledge, or does he like to make people

think he has mysterious healing powers?)

• Relating to others as equals.

For evaluating these skills and attitudes, careful observation is more helpful than

written tests. Instructors and students can observe one another when attending

the sick, explaining things to mothers and children, or carrying out other activities.

Then they can discuss their observations in the weekly evaluation meetings (see

page 9-15). (When delicate or embarrassing issues arise, it is kinder to speak to the

persons concerned in private.)

It is important that each health worker develop an attitude of self-criticism, as

well as an ability to accept friendly criticism from others. These can be developed

through evaluation sessions, private discussions, and awareness-raising dialogues

(see Ch. 26). In the long run, the development of an open, questioning attitude can

contribute more to a health worker’s success than all his preventive and curative

abilities put together.

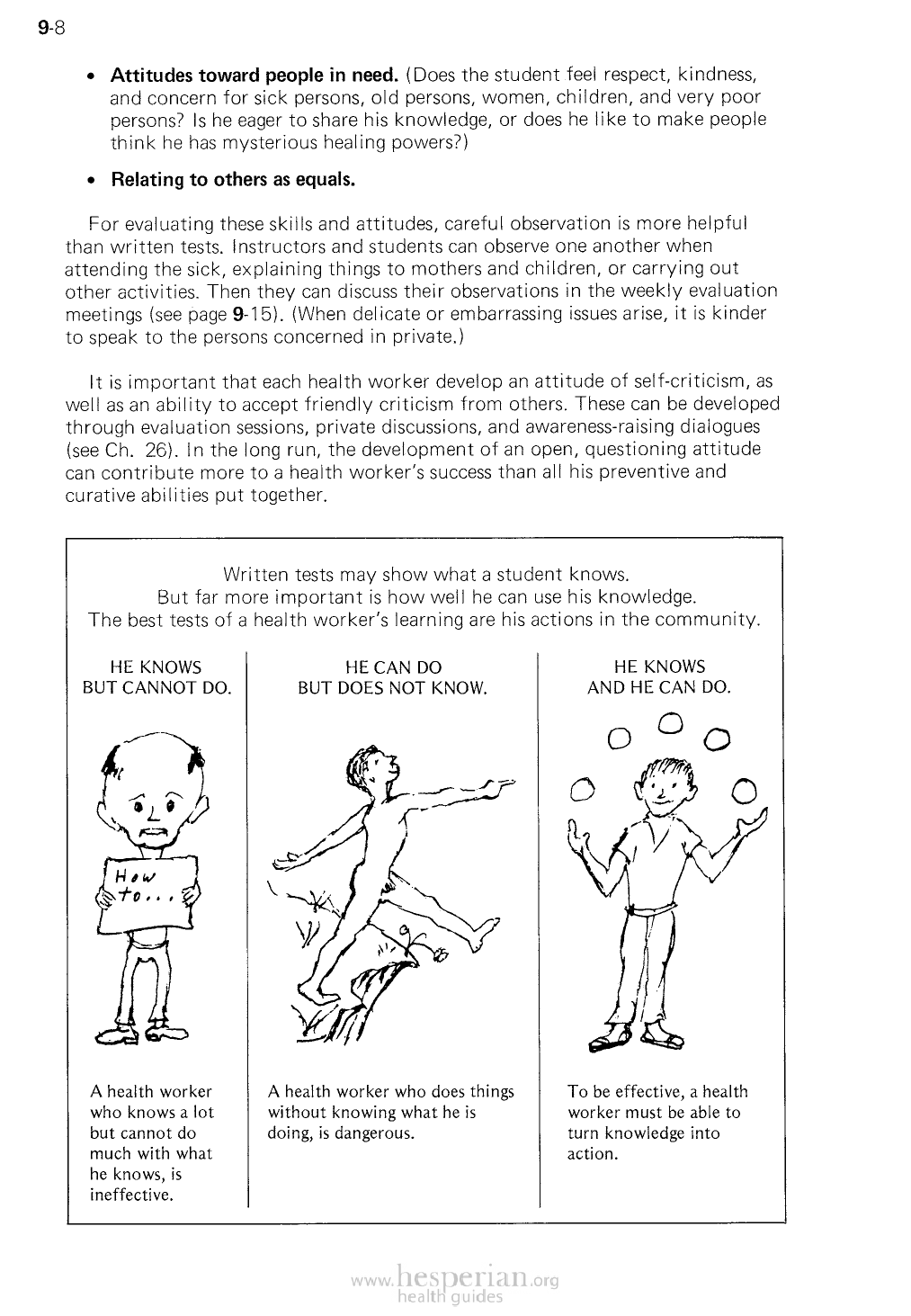

Written tests may show what a student knows.

But far more important is how well he can use his knowledge.

The best tests of a health worker’s learning are his actions in the community.

HE KNOWS

BUT CANNOT DO.

HE CAN DO

BUT DOES NOT KNOW.

HE KNOWS

AND HE CAN DO.

A health worker

who knows a lot

but cannot do

much with what

he knows, is

ineffective.

A health worker who does things

without knowing what he is

doing, is dangerous.

To be effective, a health

worker must be able

to turn knowledge into

action.