1-9

“I have an idea,” said Pepe’s father. He went

across the clearing to a pochote, or wild kapok

tree, and picked several of the large, ripe fruits.

He gathered the downy cotton from the pods,

and put a soft cushion of kapok onto the top

crosspiece of each crutch. Then he wrapped the

kapok in place with strips of cloth. Pepe tried the

crutches again and found them comfortable.

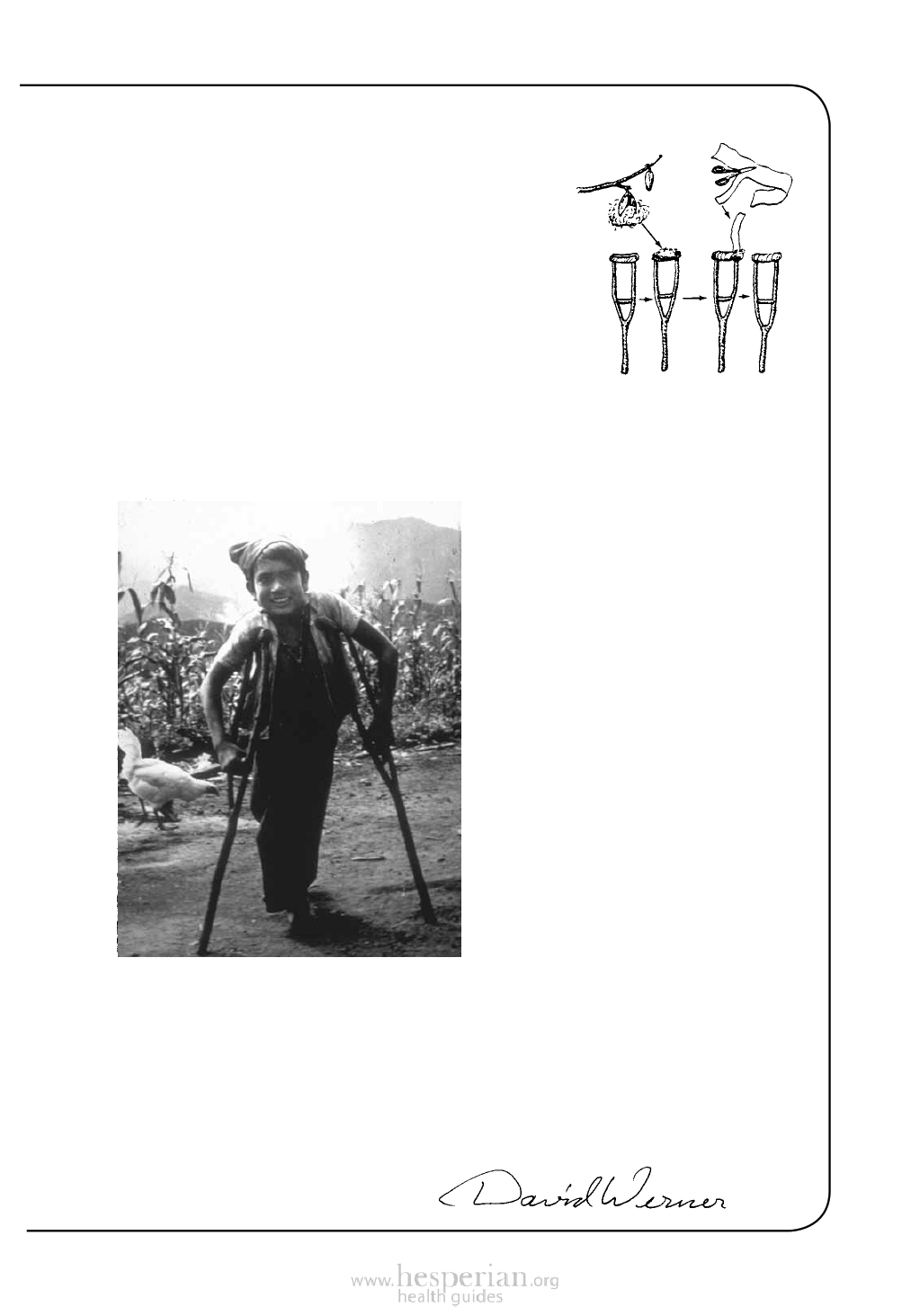

“Gosh, Dad, you really fixed them great!” cried

the boy, smiling at his father with pride. “Look

how well I can walk now!” He bounded about the

dusty patio on his new crutches.

I’m proud of you, son!” said his father, smiling too.

As the health worker was saddling his mule to leave, the whole family came

to say good-bye.

“I can’t thank you enough,” said

the father. “It’s so wonderful to see

my son able to walk upright. I don’t

know why I never thought of making

crutches before . . .”

“It’s I who must thank you,” said the

health worker. “You have taught me a

great deal.”

As the health worker rode down

the trail he smiled to himself. “How

foolish of me,” he thought, “not to

have asked the father’s advice in

the first place. He knows the trees

better than I do. And he is a better

carpenter.

“But how fortunate it is that the

crutches that I made broke. The idea for

making the crutches was mine, and the

father felt bad for not having thought of

it himself. When my crutches broke, he

made much better ones. That made us

equal again!”

So the health worker learned many things from Pepe’s father—things that he

had never learned in college. He learned what kind of wood is best for making

crutches. But he also learned how important it is to use the skills and knowledge

of the local people—important because a better job can be done, and because it

helps maintain people’s dignity. People feel more equal when each learns from

the other.

It was a lesson the health worker will always remember. I know. I was the

health worker.