26-31

But all this is more easily said than done. In spite of our good intentions, those

of us who are attracted to Freire’s method often have strong ideas of our own. We

see the world in a certain way and want others to see it as we do. Frequently, there

are deep contradictions within ourselves that we have never resolved. For example,

we may believe that each individual needs to find his own truth for himself. Yet

we feel the need to impose our own beliefs on others. And so we use—and often

misuse—the process of conscientization.

Even in the leadership and writings of the famous teachers of awareness

raising, the questions asked often have built-in answers. Look back at some of the

questions we have given as examples in this chapter. You will see how the opinions

and politics of the askers are often built into their questions. (We, the authors, often

fall into the same trap ourselves.)

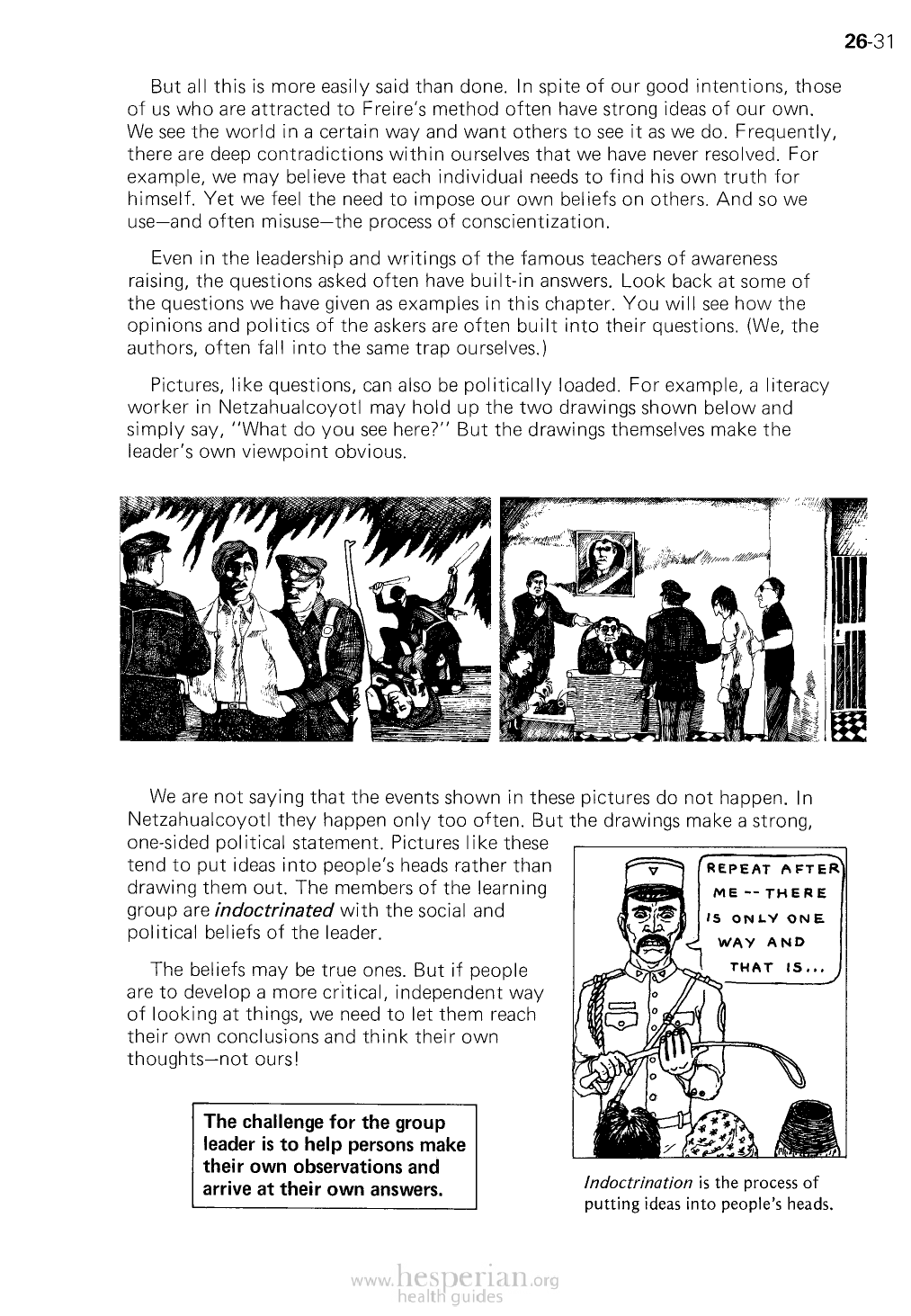

Pictures, like questions, can also be politically loaded. For example, a literacy

worker in Netzahualcoyotl may hold up the two drawings shown below and simply

say, “What do you see here?” But the drawings themselves make the leader’s own

viewpoint obvious.

We are not saying that the events shown in these pictures do not happen. In

Netzahualcoyotl they happen only too often. But the drawings make a strong,

one-sided political statement. Pictures like these

tend to put ideas into people’s heads rather than

drawing them out. The members of the learning

group are indoctrinated with the social and

political beliefs of the leader.

The beliefs may be true ones. But if people are

to develop a more critical, independent way of

looking at things, we need to let them reach their

own conclusions and think their own thoughts—

not ours!

The challenge for the group

leader is to help persons make

their own observations and

arrive at their own answers.

Indoctrination is the process of

putting ideas into people’s heads.