11-28

“Snakes and Ladders” and similar games generally have two big weaknesses as

teaching aids:

1. The messages are given to the players. The players land on the squares and

read the messages, but they do not need to think or solve anything for themselves.

It is doubtful whether such pre-packaged messages will be effective unless people

discuss them and relate them to their own lives during and after the game.

2. The game is primarily one of luck or chance. Apart from the written

messages, the game carries the unwritten message that the health of a child is

determined by lucky or unlucky rolls of the dice. Although the game is intended

to help people learn what they themselves can do to protect their children’s

health, there is a danger that it may reinforce people’s sense of ‘fatalism’. It may

make them feel that their children’s health is also a matter of luck or fortune,

outside their control.

There is one way to get around these weaknesses of the game, at least in part.

Involve student health workers in creating the game. You might start by

having them play the game from Liberia. Then together analyze its weaknesses

(for example, the attitude of blaming the victim in the statement, “A lazy

family stays poor.”). Invite the students to re-make the game, adapting it to

conditions in their own villages. See if they can think of messages that point

out both physical and social causes of ill health, and that help build people’s self-

confidence to improve their situation.

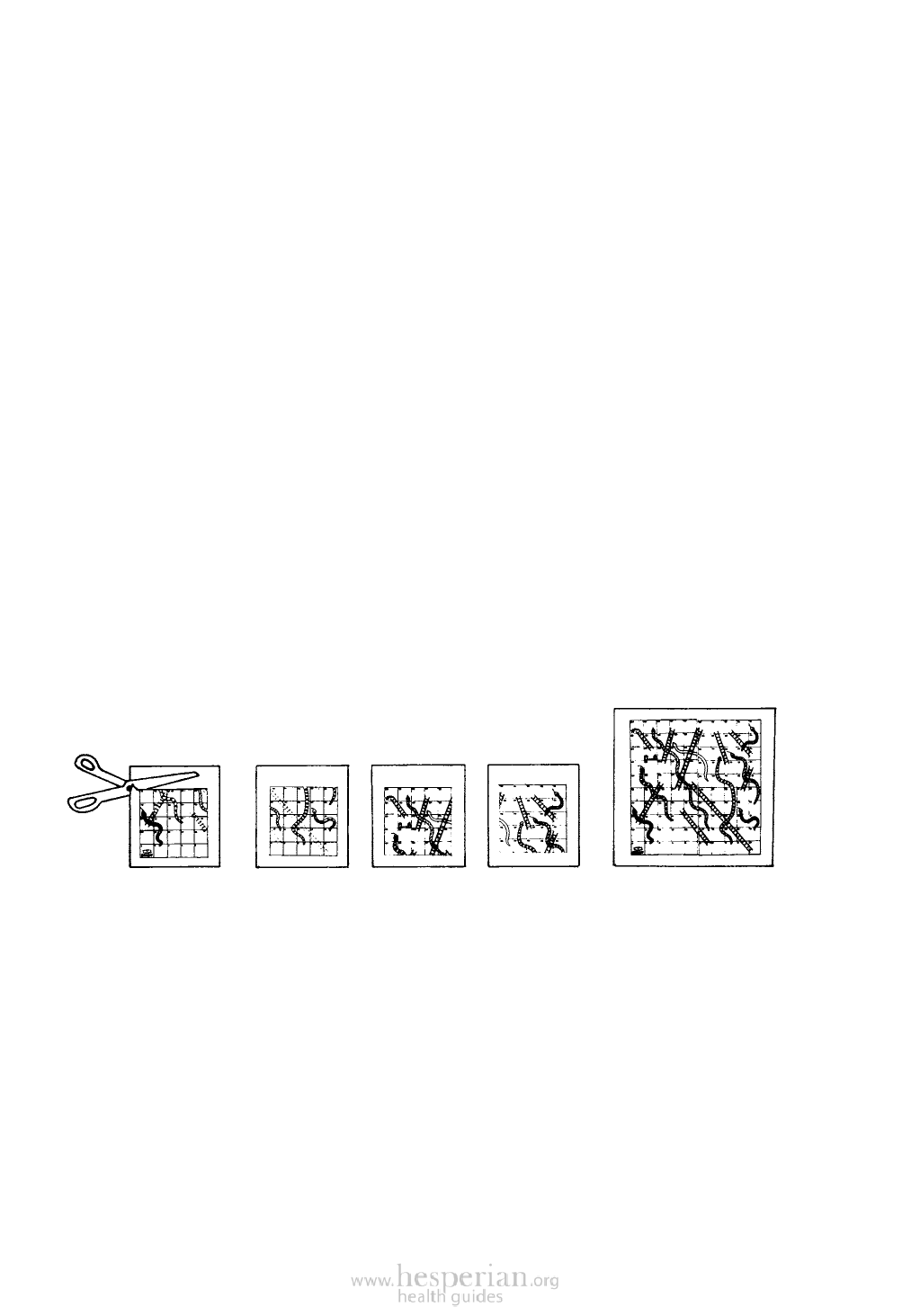

To make preparation of the game easier, you can give each health worker printed

sheets with the squares, snakes, and ladders already filled in, but without the

messages and pictures. The students can add these for themselves.

To make a large game board, students can glue 4 photocopied

sheets onto a large piece of cardboard.

By making their own games and choosing messages appropriate for their

communities, the health workers become actively involved in thinking about local

problems. The health workers can, in turn, use a similar approach with groups of

parents and children in their villages. (Children can color in the snakes.) If people

take part in creating the games they play, they will be more likely to continue to

discuss the messages they themselves have decided upon. The game becomes

less one of luck, and more one of thought, purpose, and action.

Other games similar to “Snakes and Ladders” (but more like “Monopoly”) can

get people involved in role playing. Again, dice are thrown and players advance

on a board with many squares. But the game focuses more on cultural, economic,

and political factors that affect health, and players act out the roles of poor workers,

landholders, shopkeepers, village officials, and so on. An example of such a game

is “Hacienda,” available from the Publications Department, Center for International

Education, 285 Hills South, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts

01003, USA. www.umass.edu/cie, cie@educ.umass.edu