17-9

8. Specific tests and examinations, and more questions to help find out which

of the possibilities are most likely or unlikely to be the problem.

Depending on the location, type, and duration of pain, and whether or not

there is fever, diarrhea, or vomiting, some of the possible causes may be

eliminated.

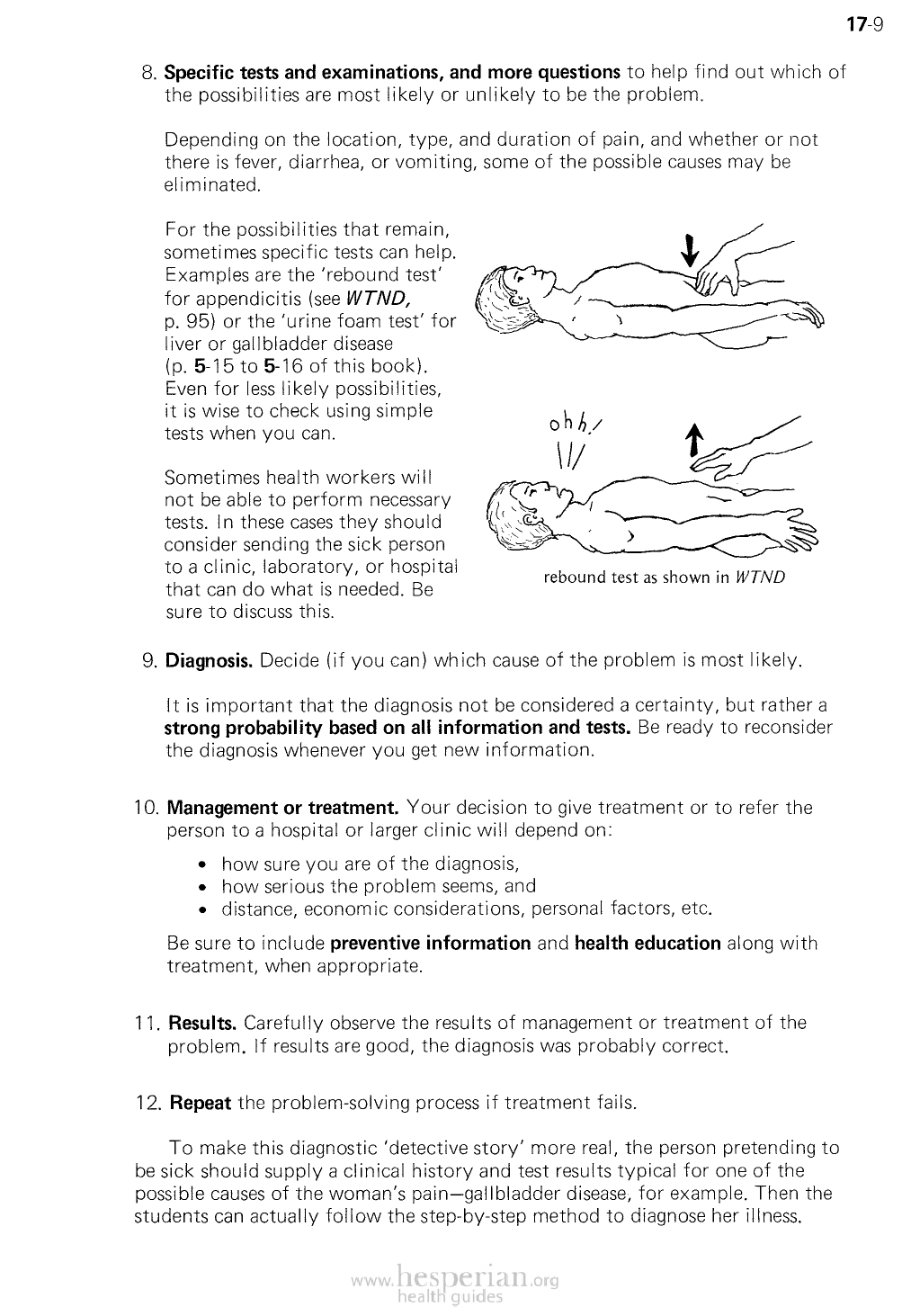

For the possibilities that remain,

sometimes specific tests can

help. Examples are the ‘rebound

test’ for appendicitis (see WTND,

p. 95) or the ‘urine foam test’ for

liver or gallbladder disease (p.

5-15 to 5-16 of this book). Even

for less likely possibilities, it is

wise to check using simple tests

when you can.

Sometimes health workers will

not be able to perform necessary

tests. In these cases they should

consider sending the sick person to

a clinic, laboratory, or hospital that

can do what is needed. Be sure to

discuss this.

rebound test as shown in WTND

9. Diagnosis. Decide (if you can} which cause of the problem is most likely.

It is important that the diagnosis not be considered a certainty, but rather a

strong probability based on all information and tests. Be ready to reconsider

the diagnosis whenever you get new information.

10. Management or treatment. Your decision to give treatment or to refer the

person to a hospital or larger clinic will depend on:

• how sure you are of the diagnosis,

• how serious the problem seems, and

• distance, economic considerations, personal factors, etc.

Be sure to include preventive information and health education along with

treatment, when appropriate.

11. Results. Carefully observe the results of management or treatment of the

problem. If results are good, the diagnosis was probably correct.

12. Repeat the problem-solving process if treatment fails.

To make this diagnostic ‘detective story’ more real, the person pretending to be

sick should supply a clinical history and test results typical for one of the possible

causes of the woman’s pain—gallbladder disease, for example. Then the students

can actually follow the step-by-step method to diagnose her illness.